Middle America, in our national imaginary, goes one of two ways: nation’s heartland or butt of the joke. It is the source of endless American symbolism1: the “spacious skies” and “amber waves of grain” in “America the Beautiful,” the drive-ins and greasy-spoon diners along Route 66, the farmers and pioneers and blue-collar workers who make up the template for an idea of “Real Americans” that still holds us in thrall. At the same time, especially after increasing political divide in the last decade, the phrase “middle America” is more often shorthand for backwards, backwater, ignorant, and flyover country (i.e. the states you’d fly over heading from one important place to another). That schizophrenic identity is particularly strong when it comes to fashion. To say (as I have), “I’m working on a project about middle American fashion” to any fellow countryman sounds like the setup to a joke—it’s just waiting for a punchline like “hm . . . what fashion?” For “middle American fashion” is a nonstarter. It is (or it’s perceived to be) five years behind trend—jeggings and polyester lace-up tops, American Eagle flannels and Nike Tempo shorts. Yet paradoxically, the clothing of the farmers, pioneers, and cowboys who settled the region continues to dominate the fashion world’s silhouettes and trend cycles. Workwear and Westernwear have never been more widespread—even while “middle America” remains a contemporary fashion punching bag.

And no one has investigated that paradox. I hope to untangle the tension inherent in middle American fashion, to answer the question, “if the heritage clothing of the Midwest still reigns in the fashion industry, why don’t middle Americans dress well?” According to the lasting nature of heritage Midwestern clothing, you’d expect the region to be constantly lauded for its native aesthetic, not ravaged for being out-of-touch or behind the trends. In my first chapter, I unpack the Midwest’s history of fashion, looking at the archetypes who settled here and the clothes they wore . . . and how those clothes came to be integral to a national idea of what an American looks like.

In 1893, historian Frederick Jackson Turner advanced an argument which would come to be known as his “frontier thesis” and which quickly became a tent pole for American historians. His “The Significance of the Frontier in American History” argued that the American frontier (the unsettled line of land west of the developed colonies) had been instrumental in developing the United States’ national character—that by constant exposure to the wilderness at the edge of society, a national spirit of ruggedness, hard work, and independence was born. The thesis was widely distributed, enormously influential, and “remains perhaps the single most important piece of American historical writing.” While aspects of Turner’s argument are biased and ethnocentric, its central tenet—that a “personality” developed in pioneers, cowboys, and farmers along the frontier has become the archetype for Americans—has passed out of academia and into artistic and popular culture. As Derek Guy puts it, “The quintessential American is not the New York financier or the Bostonian merchant, but . . . [the] cowboy on the frontier.”

It is the figures of the cowboy and the pioneer that continue to define “Americanness” to this day. To be American is to be bold, independent, hard-working, self-sufficient, democratic, maybe a little brash and swaggering . . . our national personality bases itself on a continued recycling of cowboy/pioneer qualities. Since Turner’s thesis, “Western images [have served] as shorthand symbols of patriotism, democracy, rugged individualism, and a host of other virtues,” explains “cowboy historian” Richard Slatta. And in the fashion world, the styling of Americanness—usually described under the identifier Americana—borrows heavily from that frontier aesthetic. Among the things considered Americana in fashion: Levi’s jeans, bandannas, chambray shirts, Pendleton blankets, quilts and quilting, Wrangler denim, plaid, Red Wing boots, Carhartt workwear, overalls, cowboy hats, canvas work jackets. Americana tends to be signified by an “artisan” or “handicraft” quality (as in the patchwork Ralph Lauren dress below, or in crochet work or embroidery), Western stylings (leather, fringe, denim, or beading), or a workwear/ utility silhouette (the updated “fishing gear” of the Todd Snyder x L.L. Bean collaboration, or pants with double-knees and plumber loops). Describing Americanism in fashion, dress historian Jo Ann Stabb writes, “Simplicity, functionalism, and practicality . . . define [a] U.S. aesthetic that can be traced through nineteenth- and twentieth-century fashion. This lineage connects rural and frontier clothing with US sportswear and ready-to- wear. It also reflects the eclectic patchwork of ideas that fashion has borrowed from its many source cultures, both native and nonnative—truly a melting pot that combines and synthesizes selected bits into something uniquely American.”

It’s easy to see how the American frontier—even simply the look of the American frontier—continues to be the underlying framework on which the nation arranges itself. The pioneer/cowboy identity radiates through years of Americana styling, from designer to designer, across a variety of fabrics, silhouettes, and types of clothing. And in 2022, it’s more dominant than ever, spread lavishly across fashion palates by a confluence of cultural factors. First, there was a resurgence of Western aesthetics in 2018-2019 (a re- resurgence, perhaps, as Americana aesthetics have been dug up by various subcultures since the 1970s). Second, there was the “Yeehaw Agenda,” an aesthetic trend of the same years that highlighted Black cowboys and cowgirls in popular culture and music. Finally, there is the longstanding romance between the menswear community and “blue-collar valor,” or classic elements of American workwear (all explored below). The frontier has been—and still remains—the basis of both psychological and aesthetic American-ness.

And this all-important frontier was, geographically, the American Midwest. The West and Southwest, of course (California and Montana, Arizona and Utah) boast histories of ranches and cattle herds and Levi Strauss’s initial miners-and-prospectors customer base, but the Midwest was the first frontier against which the nation defined itself. As early as 1784-1785, a first wave of settlers set out into what we now call middle America, and there was a steady trickle of migration across the Mississippi River until the 1880s, when the Oklahoma Land Run released 50,000 settlers in one day across the territory. Symbolically, the Midwest combines all the figures of Americana: the cowboy and pioneer, frontiersman and oilman— not to mention the waving-wheat, golden-plains, Route 66 imagery that’s so central to Americana. Phenomenologically and semiotically, the Midwest is the heartland of the country, the symbol of the nation and the source of the story we tell about ourselves.

The clothing of Midwesterners began to be linked to the idea of America as far back as the Depression, as historian Sandra Comstock explains. The entire country suffered in the decade of economic downturn post 1929, but the citizens of Great Plains states were beset by an additional crisis: giant dust storms that swept across the center of the nation, turning farmlands into deserts. The Dust Bowl lasted from 1930 to 1936, and as the years wore on, more and more destitute Midwestern farmers packed up their families and left the region, heading in droves to California. Beside the victims were the documentarians, trying to capture the tragic stories and noble characters affected by the crisis. What Comstock calls a “sense of societal rupture” sent “writers, artists, and singers out across the byways of the nation in search of ‘the real America.’ No image was more repetitively documented or invoked than that of working people . . . in their overalls and straight-leg blue jeans.”

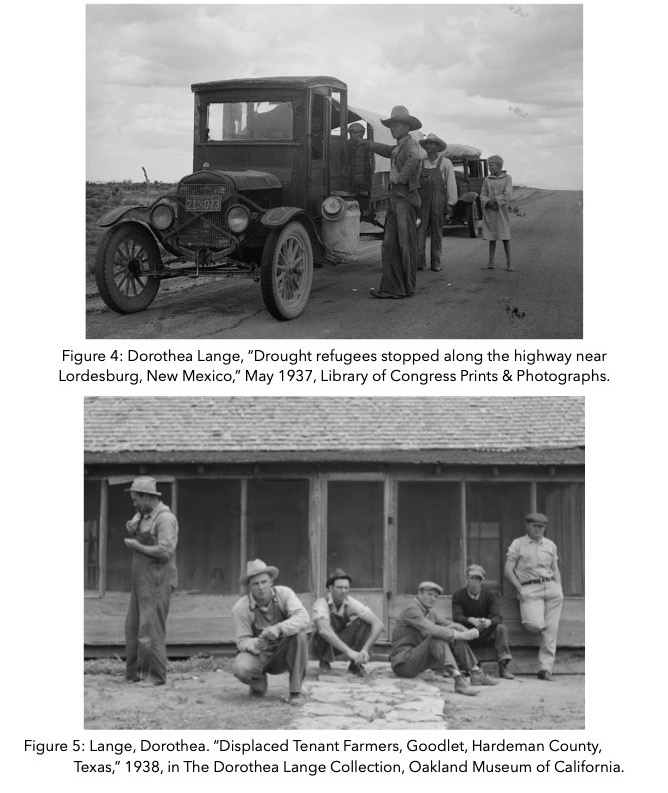

Comstock focuses on the blue jean, which she argues “became a mnemonic image that readily evoked the new iconography and rhetoric of class sweeping the US in the mid-1930s,” but it’s a natural jump to extend those evocations to the whole look of these migrant farmers—not just their jeans or overalls, but their hats, their boots, their overalls, etc. Due to the photographic coverage of Dust Bowl migrants, the clothing of Midwestern farmers/pioneers came to represent America. The below images, taken by photographer Dorothea Lange, show the types of evocative images Lange was shooting—and the hard-wearing, work- and Westernwear clothing of those pioneer/farmers.

Roland Barthes writes in The Language of Fashion that “What should really interest the researcher, historian, or sociologist, is not the passage [of a garment] from protection to ornamentation, but the tendency of every bodily covering to insert itself into an organized, formal, and normative system that is recognized by society.” In the story of Americana clothing, we can easily watch garments pass from that first, essential function (protection—as displayed in these Dust Bowl farmers’ clothing) to the second (symbolic) function, which it holds now. Barthes’s writings about fashion sent dress researchers into a fascination with semiotic decoding, with what clothing means and how that meaning is conveyed, how clothing can (or cannot) be read like a text. It is that aspect of clothing-as- symbol that is of interest in this chapter: (1) how the “look” of America came from these pioneer/cowboy figures of middle America, (2) how the same look has been reused and recycled through American fashion since, and (3) how those garments now carry the so- called “American values” attributed to those first pioneer/cowboys. Fashion has been called a kind of “connective tissue of our cultural organism,” and while normally fashion connects and defines subcultures, Americana stylings have, in a curious way, become a connective tissue for the whole of the American people. The pioneers, farmers, roughnecks, rednecks, cowboys, oilies, and blue-collar workers of our past gave the nation a sartorial heritage rooted in middle America.

excerpt from “How to Dress Well in Middle America, or, Why We Don’t and Why That Doesn’t (Quite) Make Sense,” postgraduate dissertation for the Royal College of Art, Caroline White, December 2022.